The Silicon Valley Bank failure strikes me as a colossal failure of bank regulation, and instructive on how rotten the whole edifice is. I write this post in an inquisitive spirit. I don't know the details of how SVB was regulated, and I hope some readers do and can chime in.

As reported so far by media, the collapse was breathtakingly simple. SVB paid a bit higher interest rates than the measly 0.01% (yes) that Chase offers. It attracted large deposits from venture capital backed firms in the valley. Crucially, only the first $250,000 are insured, so most of those deposits are uninsured. The deposits are financially savvy customers who know they have to get in line first should anything go wrong. SVB put much of that money into long-maturity bonds, hoping to reap the difference between slightly higher long-term interest rates and what it pays on deposits. But as we've known for hundreds of years, if interest rates rise, then the market value of those long-term bonds fall. Now if everyone comes asking for their money back, the assets are not worth enough to pay everyone back.

In sum, you have "duration mismatch" plus run-prone uninsured depositors. We teach this in the first week of an MBA or undergraduate banking class. This isn't crypto or derivatives or special purpose vehicles or anything fancy.

Where were the regulators? The Dodd Frank act added hundreds of thousands of pages of regulations, and an army of hundreds of regulators. The Fed enacts "stress tests" in case regular regulation fails. How can this massive architecture fail to spot basic duration mismatch and a massive run-prone deposit base? It's not hard to fix, either. Banks can quickly enter swap contracts to cheaply alter their exposure to interest rate risk without selling the whole asset portfolio.

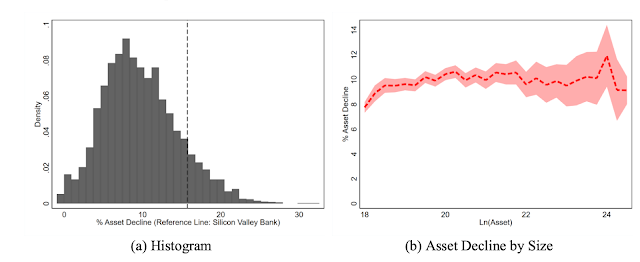

Michael Cembalist assembled numbers. This wasn't hard to see.

Even Q3 2022 -- a long time ago -- SVB was a huge outlier in having next to no retail deposits (vertical axis, "sticky" because they are insured and regular people), and a huge asset base of loans and securities.

Michael then asks

.. how much duration risk did each bank take in its investment portfolio during the deposit surge, and how much was invested at the lows in Treasury and Agency yields? As a proxy for these questions now that rates have risen, we can examine the impact on Common Equity Tier 1 Capital ratios from an assumed immediate realization of unrealized securities losses ... That’s what is shown in the first chart: again, SVB was in a duration world of its own as of the end of 2022, which is remarkable given its funding profile shown earlier.

Again, in simpler terms. "Capital" is the value of assets (loans, securities) less debt (mostly deposits). But banks are allowed to put long-term assets into a "hold to maturity" bucket, and not count declines in the market value of those assets. That's great, unless people knock on the door and ask for their money now, in which case the bank has to sell the securities, and then it realizes the market value. Michael simply asked how much each bank was worth in Q42002 if it actually had to sell its assets. A bit less in each case -- except SVB (third from left) where the answer is essentially zero. And Michael just used public data. This is not a hard calculation for the Fed's team of dozens of regulators assigned to each large bank.

Perhaps the rules are at fault? If a regulator allows "hold to maturity" accounting, then, as above, they might think the bank is fine. But are regulators really so blind? Are the hundreds of thousands of pages of rules stopping them from making basic duration calculations that you can do in an afternoon? If so, a bonfire is in order.

This isn't the first time. Notice that when SBF was pillaging FTX customer funds for proprietary trading, the SEC did not say "we knew all about this but didn't have enough rules to stop it." The Bank of England just missed a collapse of pension funds who were doing exactly the same thing: borrowing against their long bonds to double up, and forgetting that occasionally markets go the wrong way and you have to sell to make margin calls. (That's week 2 of the MBA class.)

Ben Eisen and Andrew Ackerman in WSJ ask the right question (10 minutes before I started writing this post!) Where Were the Regulators as SVB Crashed?

“The aftermath of these two cases is evidence of a significant supervisory problem,” said Karen Petrou, managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics, a regulatory advisory firm for the banking industry. “That’s why we have fleets of bank examiners, and that’s what they’re supposed to be doing.”

The Federal Reserve was the primary federal regulator for both banks.

Notably, the risks at the two firms were lurking in plain sight. A rapid rise in assets and deposits was recorded on their balance sheets, and mounting losses on bond holdings were evident in notes to their financial statements.

moreover,

“Rapid growth should always be at least a yellow flag for supervisors,” said Daniel Tarullo, a former Federal Reserve governor who was the central bank’s point person on regulation following the financial crisis...

In addition, nearly 90% of SVB’s deposits were uninsured, making them more prone to flight in times of trouble since the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. doesn’t stand behind them.

90% is a big number. Hard to miss. The article echoes some confusion about "liquidity"

SVB and Silvergate both had less onerous liquidity rules than the biggest banks. In the wake of the failures, regulators may take a fresh look at liquidity rules,...

This is absolutely not about liquidity. SBV would have been underwater if it sold all its securities at the bid prices. Also

Silvergate and SVB may have been particularly susceptible to the change in economic conditions because they concentrated their businesses in boom-bust sectors...

That suggests the need for regulators to take a broader view of the risks in the financial system. “All the financial regulators need to start taking charge and thinking through the structural consequences of what’s happening right now,” she [Saule Omarova] said

Absolutely not! I think the problem may be that regulators are taking "big views," like climate stress tests. This is basic Finance 101 measure duration risk and hot money deposits. This needs a narrow view!

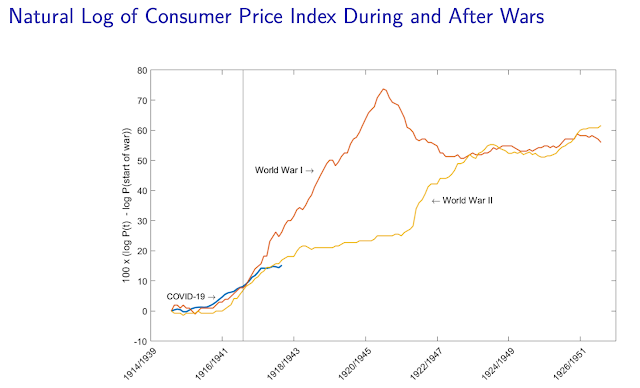

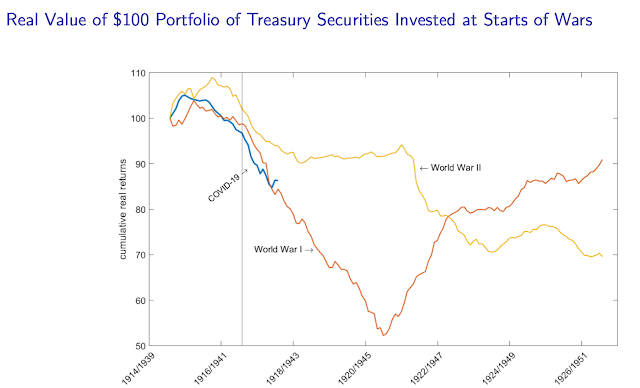

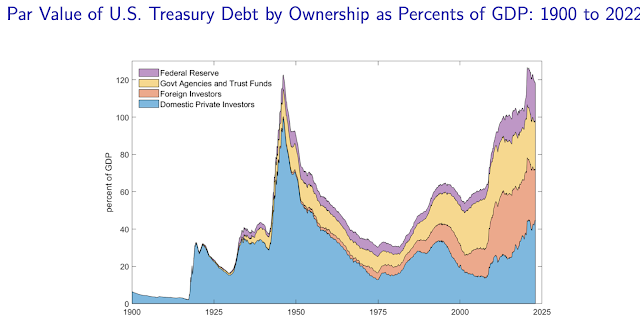

There is a larger implication. The Fed faces many headwinds in its interest rate raising effort. For example, each point of higher real interest rates raises interest costs on the debt by about $250 billion (1 percent x 100% debt/GDP ratio). A rate rise that leads to recession will lead to more stimulus and bailout, which is what fed inflation in the first place.

But now we have another. If the Fed has allowed duration risk to seep in to the too-big to fail banking system, then interest rate rises will induce the hard choice between yet more bailout and a financial storm. Let us hope the problem is more limited - as Michael's graphs suggest.

Why did SVB do it? How could they be so blind to the idea that interest rates might rise? Why did Silicon Valley startups risk cash, that they now claim will force them to bankruptcy, in uninsured deposits? Well, they're already clamoring for a bailout. And given 2020, in which the Fed bailed out even money market funds, the idea that surely a bailout will rescue us should anything go wrong might have had something to do with it.

(On the startup bailout. It is claimed that the startups who put all their cash in SVB will now be forced to close, so get going with the bailout now. It is not startups who lose money, it is their venture capital investors, and it is they who benefit from the bailout.

Let us presume they don't suffer sunk cost fallacy. You have a great company, worth investing $10 million. The company loses $5 million of your cash before they had a chance to spend it. That loss obviously has nothing to do with the company's prospects. What do you do? Obviously, pony up another $5 million and get it going again. And tell them to put their cash in a real bank this time.)

How could this enormous regulatory architecture miss something so simple?

This is something we should be asking more generally. 8% inflation. Apparently simple bank failures. What went wrong? Everyone I know at the Fed are smart, hard working, honest and dedicated public servants. It's about the least political agency in Washington. Yet how can we be seeing such simple o-ring level failures?

I can only conclude that this overall architecture -- allow large leverage, assume regulators will spot risks -- is inherently broken. If such good people are working in a system that cannot spot something so simple, the project is hopeless. After all, a portfolio of long-term treasuries is about the safest thing on the planet -- unless it is financed by hot money deposits. Why do we have teams of regulators looking over the safest assets on the planet? And failing? Time to start over, as I argued in Towards a run free financial system

Or... back to my first question, am I missing something?

****

Updates:

A nice explainer thread (HT marginal revolution). VC invests in a new company. SVB offers an additional few million in debt, with one catch, the company must use SVB as the bank for deposits. SVB invests the deposits in long-term mortgage backed securities. SVB basically prints up money to use for its investment!

"SVB goes to founders right after they raise a very, very expensive venture round from top venture firms offering:

- 10-30% of the round in debt

- 12-24 month term

- interest only with a balloon payment

- at a rate just above prime

For investors, it also seems like a no-downside scenario for your portfolio: Give up 10-25 bps in dilution for a gigantic credit facility at functionally zero interest rate.

If your PortCo doesn't need it, the cash just sits. If they do, it might save them in a crunch. The deals typically have deposit covenants attached. Meaning: you borrow from us, you bank with us.

And everyone is broadly okay with that deal. It's a pretty easy sell! "You need somewhere to put your money. Why not put it with us and get cheap capital too?"

Update:

1) Old Eagle Eye's comment below is fascinating. I am getting the sense that the rules actually preclude putting 2+2=4 together here. Copied here in toto

SIVB did have a hedge put on during 2022, but it was limited to its available-for-sale securities ("AFS"). It was precluded from hedging its interest rate risk in held-to-maturity securities ("HTM") by U.S. GAAP rules. [My emphasis] Here is the explanation found at PwC:

[PWC Viewpoint Commentary: "The notion of hedging the interest rate risk in a security classified as held to maturity is inconsistent with the held-to-maturity classification under ASC 320, which requires the reporting entity to hold the security until maturity regardless of changes in market interest rates. For this reason, ASC 815-20-25-43(c)(2) indicates that interest rate risk may not be the hedged risk in a fair value hedge of held-to-maturity debt securities." "ASC 815-20-25-12(d) provides guidance on the eligibility of held-to-maturity debt securities for designation as a hedged item in a fair value hedge."]

[Extracted subsection:

"Chapter 6: Hedges of financial assets and liabilities.

"6.4 Hedging fixed-rate instruments

"6.4.3.4 Hedging held-to-maturity debt securities

"ASC 815-20-25-12(d)

"If the hedged item is all or a portion of a debt security (or a portfolio of similar debt securities) that is classified as held to maturity in accordance with Topic 320, the designated risk being hedged is the risk of changes in its fair value attributable to credit risk, foreign exchange risk, or both. If the hedged item is an option component of a held-to-maturity security that permits its prepayment, the designated risk being hedged is the risk of changes in the entire fair value of that option component. If the hedged item is other than an option component of a held-to-maturity security that permits its prepayment, the designated hedged risk also shall not be the risk of changes in its overall fair value."]

Source: PWC Viewpoint (viewpoint.pwc.com) Publication date: 31 Jul 2022

https://viewpoint.pwc.com/dt/us/en/pwc/accounting_guides/derivatives_and_hedg/derivatives_and_hedg_US/chapter_6_hedges_of__US/64_hedging_fixedrate_US.html

Update 2: Thanks to anonymous below for a pointer to

a good New York Times article about SVB, what the Fed knew and when. Apparently the bank's supervisors knew about problems for a long time before the bank failed. Whether this is good or bad news for the regulatory project I leave to you.